Jagran Josh

3.2 ELECTRIC CURRENT

Current through a given area of a conductor is the net charge passing per unit time through the area.

3.3 ELECTRIC CURRENTS IN CONDUCTORS

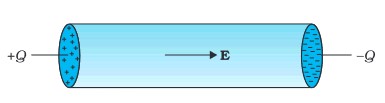

Charges +Q and –Q put at the ends of a metallic cylinder. The electrons will driftv because of the electric field created to neutralise the charges. The current thus vwill stop after a while unless the charges +Q and –Q are continuously replenished.

3.4 OHM’S LAW

Ohm’s law states that

V ∝ I

or, V = R I

The constant of proportionality R is called the resistance of the conductor.

Doubling the length of a conductor doubles the resistance.

Halving the area of the cross-section of a conductor doubles the resistance.

hence for a given conductor:

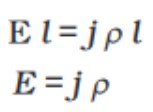

where the constant of proportionality r depends on the material of the conductor but not on its dimensions. r is called resistivity.

Current per unit area (taken normal to the current), I/A, is called current density and is denoted by j.

Magnitude E of uniform electric field

3.5 DRIFT OF ELECTRONS AND THE ORIGIN OF RESISTIVITY

Drift Velocity: Electrons move with an average velocity which is independent of time, although electrons are accelerated.

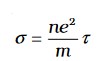

Conductivity

3.5.1 Mobility

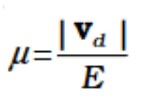

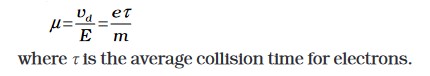

Mobility (m) defined as the magnitude of the drift velocity per unit electric field:

Also,

3.6 LIMITATIONS OF OHM’S LAW

Ohm’s law is obeyed by many substances, but it is not a fundamental law of nature. It fails if

(a) V depends on I non-linearly.

(b) the relation between V and I depends on the sign of V for the same absolute value of V.

(c) The relation between V and I is non-unique.

An example of (a) is when r increases with I (even if temperature is kept fixed). A rectifier combines features (a) and (b). GaAs shows the feature (c).

3.7 RESISTIVITY OF VARIOUS MATERIALS

Electrical resistivity of substances varies over a very wide range. Metals have low resistivity, in the range of 10–8 W m to 10–6 W m. Insulators like glass and rubber have 1022 to 1024 times greater resistivity. Semiconductors like Si and Ge lie roughly in the middle range of resistivity on a logarithmic scale.

3.8 TEMPERATURE DEPENDENCE OF RESISTIVITY

In the temperature range in which resistivity increases linearly with temperature, the temperature coefficient of resistivity a is defined as the fractional increase in resistivity per unit increase in temperature.

![]()

Unlike metals, the resistivities of semiconductors decrease with increasing temperatures.

![]()

3.9 ELECTRICAL ENERGY, POWER

in an actual conductor, an amount of energy dissipated as heat in the conductor during the time interval Dt is DW = IVDt

The energy dissipated per unit time is the power dissipated P = DW/Dt and we have P = IV

Using, ohm’s law

![]()

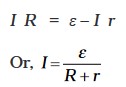

3.10 CELLS, EMF, INTERNAL RESISTANCE

A simple device to maintain a steady current in an electric circuit is the electrolytic cell.

EMF is the potential difference between the positive and negative electrodes in an open circuit, i.e., when no current is flowing through the cell.

EMF is a potential difference and not a force.

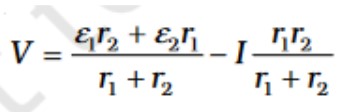

V = E – Ir

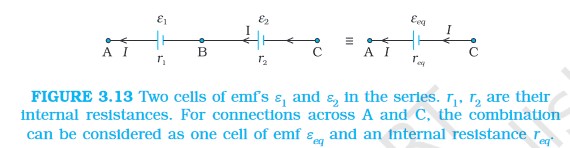

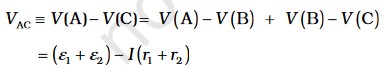

3.11 CELLS IN SERIES AND IN PARALLEL

3.12 KIRCHHOFF’S RULES

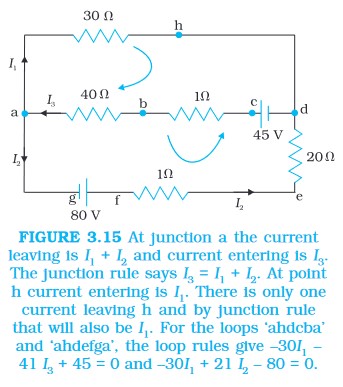

Junction rule: At any junction, the sum of the currents entering the junction is equal to the sum of currents leaving the junction.

Loop rule: The algebraic sum of changes in potential around any closed loop involving resistors and cells in the loop is zero.

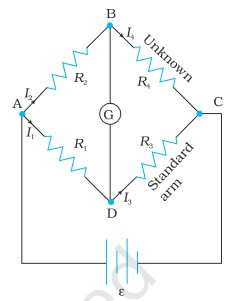

3.13 WHEATSTONE BRIDGE

A practical device using this principle is called the meter bridge.

#Current #Electricity #Class #Notes #CBSE #12th #Physics #Chapter #Download #PDF